Kenelm Digby 1603-1665

Sir KENELM DIGBY 1603-1665

Biographical Note

Born at Gayhurst, Buckinghamshire, son of Sir Everard Digby, who was executed for his part in the Gunpowder Plot in 1606. The family were recusant gentry with a long lineage. Entered Gloucester Hall, Oxford 1615 as a pupil of Thomas Allen (q.v.); left without graduating 1619, to tour Europe. After extensive travels he became involved in the 1623 negotiations in Madrid around Charles I’s proposed marriage to the Infanta; on returning to England, Digby was knighted and made a gentleman of the Prince’s privy chamber.

After leading a privateering expedition to Iskenderun in 1628, Digby held various appointments at Charles I’s court. The death of his wife Venetia in 1633 had a profound effect and he withdrew to Gresham College to pursue scientific and alchemical experiments. He moved to Paris, 1635-38, and then alternated between London, Paris and Rome during the ensuing Civil War and Interregnum period, including a period of imprisonment in London. He was involved, during these years, in a variety of ambassadorial schemes between the English government, Charles II’s court in exile, and the papacy. He returned to England in 1660, with a house and laboratory in Covent Garden, and was elected a member of the Royal Society.

Digby had extensive literary and scientific connections and was much admired in his day as a virtuoso. He was a friend of Ben Jonson and helped to prepare the 1640 edition of Jonson’s works for the press. He was a poet himself but he was mainly regarded as a scientist and natural philosopher; he corresponded with Descartes and published various works including Two treatises, in the one of which the nature of bodies, in the other the nature of man’s soul is looked into (1644) and A discourse concerning the nature of plants (1661). His Choice and experimented receipts in physick and chemistry appeared posthumously in 1668.

Books

Digby had an active interest in books, from both a scholarly and bibliophilic perspective, throughout his life and he assembled extensive collections. His correspondence, which survives in various places (including BL Add. mss 38175, 48146) includes numerous references to books and their acquisition. The library acquired up to the time of the Civil War, which was augmented by the bequest of Thomas Allen’s books, was apparently dispersed and possibly destroyed some time after 1643. Thereafter he assembled a library in Paris, which was left there on his return to England in 1660; he intended to return to it, but his death intervened. The collection, estimated at ca. 3500 volumes, was claimed as French crown property and mostly sold in Paris; Digby’s cousin George, 2nd Earl of Bristol (1612-77) purchased much of it and brought it back to England, where it was subsequently auctioned, along with the Earl’s own books and “the library of another learned person” in London, 19 April 1680. The sale catalogue includes 3685 lots, divided into Latin theology (414), Latin philology (843), Medicine (315), Mathematics (214), French books (434), Spanish books (135), Italian books (404), English books (926), plus 88 bundles of stitched pamphlets, 25 bound volumes of pamphlets, 10 “libri incompacti” and 69 manuscripts. Although the catalogue states that “the great part … were the curiosities collected by the learned Sr. Kenelme Digby”, it is not possible to separate the books out with certainty. The sale made £908 4s 10d. A manuscript catalogue of Digby’s French library, now in the Bibliothèque Nationale shows that it was wide ranging in subjects and languages.

Digby was persuaded by Laud to donate the manuscripts he inherited from Thomas Allen, together with some of his own, to the Bodleian Library in 1634. He also gave 36 Aramaic and Hebrew manuscripts to St John’s College, Oxford in 1639, which became joined with a gift from Laud, and were actually received by the Bodleian. In 1655 he donated ca.40 printed books, mostly theological, to Harvard University.

In 1634 Digby commissioned the making of a book to celebrate the history of the family; this is described as having involved great expense, involving exhaustive documentation contained in a large vellum book, elaborately decorated, and bound with silver furniture. This was bequeathed to his son John, and is recorded as having been seen and exhibited in the 18th century, but has since been lost. Examples: BL C.67.i.1, C.67.e.9; Cambridge UL C*.12.10, Rel.d.54.2; Durham UL Bamburgh Sel.36; Bodleian H.1.15.Art.Seld; Maggs 1212 (1996)/33.

Characteristic Markings

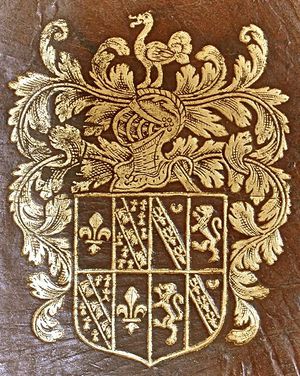

Digby’s books are often readily recognisable from the various manifestations of his arms or monogram found on the boards or spine; he used 4 versions of his arms, two monogram stamps (one KD, one KDV adding V for his wife Venetia), and a fleur-de-lys in two sizes. Many of his bindings are French, in goatskin or calf. He commonly inscribed his titlepages with his name, and sometimes added a motto, “Vacate et videte” or “Vindica te tibi”. These books date from his “French” library, of course. The manuscripts he inherited from Thomas Allen, were reorganised and bound on his instructions before being given to the Bodleian.

Sources

- British Armorial Bindings.

- Beadle, R. Medieval English manuscripts at auction, 1676-c.1700, The Book Collector, 53 (2004), 46-63.

- Bibliotheca Digbeiana, [London, 1680], ESTC r26083.

- Craster, H. ‘Digby mss’, Bodleian Quarterly Record, 2 (1919) 239-41.

- Foster, Michael. "Digby, Sir Kenelm (1603–1665), natural philosopher and courtier." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Macray, W. D. Annals of the Bodleian Library. 2nd edn, Oxford, 1890. 78-81.

- Mandelbrote, G. The organisation of book auctions in late seventeenth-century London, in R. Myers (ed), Under the hammer, London, 2001, 15-36.

- Petersson, R. Sir Kenelm Digby: the ornament of England, London, 1956 (particularly pt.III ch.2, “Red morocco”).

- Philip, I. The Bodleian Library in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Oxford, 1983.

- Sheppard, L. ‘A vellum copy of the Great Bible, 1539’, National Library of Wales Jnl 1 (1939-40), 9-19.

- Starks, C. H. ‘Work in progress: Richard Hunt’s revision of the Digby catalogue’, in A. C. de la Mare and B. Barker-Benfield (eds), Manuscripts at Oxford, 1980, 118-121.